Waterworks

The Spring and the Fountain of Klepsydra

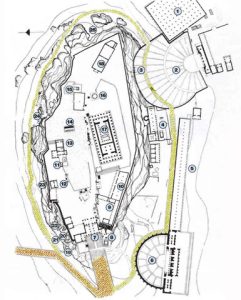

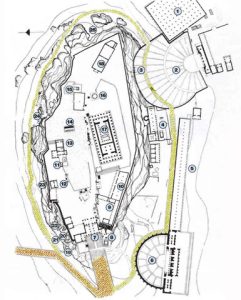

To the northwest of the Acropolis, at the point where the ancient streets Panathenaic Way and Peripatos street met, stands the Klepsydra, an ancient fountain house exploiting an underground spring that was discovered inside a cave. This is the best known and most important fountain and spring of the Acropolis.

Hydria Virtual Museum

The spring in the cave was discovered in the second half of the 13th century BC during work on the fortifications of the Acropolis. But even before this time, during the Neolithic period, the inhabitants of Athens were aware of a rich underground water vein existing in the same area. Thus, they opened 22 wells (3 to 5 m deep) in order to exploit it. The area was originally named after the nymph Empedo, who was associated with water.

During the fortification works it was ensured that both this cave spring and the Asklepieion spring house (see below) on the other side of the Acropolis would be enclosed in the walls, to provide access to the valuable resource within the walls. Hence, the Athenians systematically exploited the cave spring ever since, which to a great extent remained in its natural state. The main construction work to exploit the site, i.e. the actual building of the fountain house and the auxiliary buildings was carried out much later, in the 5th century BC.

The fountain house was actually built under Kimon’s rule in the period 470-460 BC. It was a simple construction, built with hard compact blocks of porous stone (0,40 m × 1,13 m each) in accordance to the isodomic system. The floor plan was rectangular, measuring approximately 8 m × 7 m. At the back of the cave a 4m deep reservoir was built, a “box-like” construction adjacent to the natural water basin of the cave, measuring a surface ~ 4,5 m × 2,2 m. At an intermediate level, between the reservoir and the ground level outside the cave, an L-shaped platform was formed to facilitate the drawing of water. A built stairway provided access to this platform from the ground level outside the cave (height difference of 2.30 m). Beside the spring fountain a flat yard was constructed to collect the rainwater as a supplementary water source, especially in periods when the spring was low in supply.

Actually, the meaning of the word klepsydra (κλεψύδρα) in Greek is “stolen water” and it was given to the spring because its water disappeared from time to time, mainly due to frequent landslides that altered the flow of the ground water. The ancient yard is still visible today.

In order to defend the fountain against a possible collapse of the rock lying above, it was reinforced with three wooden braces, whose sockets are still visible today from the exterior of the west wall. Evenso, after the 1st century AD and for many centuries, several re-construction works took place due to frequent landslides. During the 1stcentury AD, a severe landslide of falling rocks blocked the entrance to the L shaped platform. From then on, a new entrance to the fountain on the north side was created, leaving the western part of the yard in disuse.

This new entrance was also blocked by yet another landslide in the late 2nd century AD depriving access to the spring from the Panathenaic Way. This called for re-construction works yet again. A well was opened in order to draw water through the fallen rock and above it a solid vaulted construction was created for protection. From this point, an ascending vaulted corridor (70 stairs) led to the foot of the bastion below the Propylaia, being the only way to access the spring-house.

The Klepsydra spring was used throughout the Byzantine period (4th to 15th century AD) and was again repaired during the Frankish occupation (mid 13th century AD). The spring was completely abandoned during the Turkish occupation until it was rediscovered in 1822 by the Greek archaeologist Mr. Kyriakos Pittakis.

The Asklepieion spring house

On the south slope of the Acropolis stand the remains of the temple of Asklepios, the god of healing for the Ancient Greeks. To the west of the Ionic stoa, one of the auxiliary buildings of the temple, a small fountain house has been discovered, dating from the end of the 6th century BC.

It was a square room housing a square basin, 3.10 m deep, from where the spring water was drawn. At the bottom of this basin there was a small well 1.25 m deep, with masonry walls and a small opening to the south, in order to let in the water from the spring. The basin was made of masonry walls, built with polygonal Kara limestone, while the part of the fountain above ground level was built with Acropolis limestone and was 0.50 m thick. The width of the fountain house must have been ~ 3 m internally and therefore ~4 m externally. It is believed that the entrance to the fountain was through a kind of porch, which was demolished in the 4th century BC, a time when the well was covered with earth and no longer used.

Hydria Virtual Museum

The northeast corner of the draw basin is preserved and the visitor today can see the part of the Acropolis cliff that was removed in order to house the basin, although it is covered with vegetation nowadays. In the opposite direction, the western part of the basin was destroyed when a byzantine vaulted cistern was constructed.

In this area a boundary stone was found that is believed to date from the late 5th century BC presumably to mark the boundaries of the fountain when the Asklepios temple was founded. At the same site, various votive reliefs with nymphs were also found proving that the spring was dedicated to the nymphs, and possibly a place of worship of Pan, from the 5th century BC onward. In addition, in the same area a large altar-table was discovered (made of marble from mount Ymittos) bearing the names of the gods Hermes, Aphrodite and Isis, which perhaps signifies that they were also worshipped in the spring house, even though these later inscriptions may be attributed to the remains of two other temples found nearby.

In the early Christian period, around 450 AD the temple of Asklepios was demolished to be replaced by a Christian temple that was built using the same building material. Interestingly, this new church was devoted to Saints Anargyroi, two doctor brothers also considered saints of healing, and the spring kept being used for its “holy” water. This is a common phenomenon in the transition from idolatry to Christianity in Greece, in that the ancient Gods are replaced by Christian Saints who are however considered as the “guardian” of the same attribute, i.e. health, travel, family, crops, etc.

Hydria Virtual Museum

The Mycenean Spring Fountain

On the north slope of the Acropolis, inside the cave of Ersis (until recently it was attributed to the nymph Aglauros), an impressive structure exists for a spring that was probably discovered during the fortification works of the Acropolis (on the Pelasgic wall, second half of the 13th century BC) for the protection against an imminent invasion by the Dorians.

The spring construction, in use only for a short time during the Mycenaean period, is believed to be one the first technical works to ensure water supply to the city. Mycenaean pottery found in it, dating from the second half of the 13th century BC and not later, indicates theshort period of use that was not longer than 30-40 years. In all probability a landslide or earthquake must have blocked it.

The entrance to the cave is at the level of the Parthenon, west of the Arrhephorion, a small square building where young virgin women (Arrhephoroi) used to weave the mantle/veil of the goddess (Athena) for the well known Panathenea festival and other rituals.

Hydria Virtual Museum

The cave is an impressive, almost vertical fissure, 35 m deep, with a series of stairways. In the upper part, the rock was carved in order to support wooden stairs, while in the lower part, the stairs were built using large schist slabs placed on rubble, which was supported by wooden beams.

Hydria Virtual Museum

The stairway ended at the boundary between the upper layer of limestone rock and the underlying layer of marl rock. In this lower part of the cave there was a well, 9 m deep, that provided access to an underground vein of water. The diameter of the well was ~2 m at the surface and 4 m near its bottom.

Hydria Virtual Museum

The spring ceased to be in use, as its lower part was covered with soil probably due to an earthquake or landslide. However, the upper part of the cave remained intact and as it has a second exit to the north slope of the rock, it was used during antiquity and in subsequent periods, as a secret passage. Actually, this passage is linked to a heroic moment of recent Greek history. During the Nazi occupation in 1941 two students, Manolis Glezos and Apostolos Santas, used this passage to reach the Acropolis and sucessfully take down the Nazi flag.