PEOPLE / CULTURE

Augustus’ inscription of the Serino aqueduct

Based on an inscription dating from the 4th century AD Augustus was initial builder of the Serino Aqueduct and Claudius was responsible for its restoration and possibly the extension to Miseno.

The inscription reads in Latin:

Dd. nn. Fl. Constantinus Max. Pius Felix Victor Aug. et Fl. Iul. Crispus et Fl. Cl. Constantns, nobb. Caess. fontis Augustei aquaeductum longa incuria et vetustate conrptm pro magnificentia liberalitatis cons[v]etae sua pecunia r[e]fci iussernt et usui ci[vi]tat[iu]m infra scriptarum reddiderunt, dedicante Ceionio Iuliano uccons. camp. curante pontiano u. p. praep. eiusdem aquaeductus, nomina civitatium Puteolana, Neapolitana, Nolana, Atellana, Cumana, Acerrana, Baiana, Misenum

The inscription reads in English:

Our Lords the Emperor Constantine the great, pious, successful and victorious and Flavius Julius Crispus and Flavius Claudius Constantinus, most noble Caesars, have ordered the aqueduct of the Augustean spring that had been ruined by long neglect and old age to be restored on their costs by their usual greatness and generosity, and they have given back its use to the towns described below. Inaugurated by Ceionius Julianus, most noble Lord, consul [governor] of Campania. Carried out by Pontianus, most excellent Lord and overseer of the said aqueduct. The names of the towns are Puteoli, Naples, Nola, Atella, Cuma, Acerra, Baia and Miseno.

(source: www.romanaqueducts.info)

The same watering for different ages

Starting from Greek and Roman times, and, as the population of Naples grew in the following centuries, an incredible number of wells and cisterns were built. Many of Naples’ palaces were erected above these sites, constructed using the deposits of tuff quarried from ever widening bottle shaped cavities beneath them, with a narrow top and wide bottom, forming a bulbous cavity.

The sloping sides of the bottle shaped quarried void maintained the structural integrity of the ground beneath the huge buildings. The cavities were then cleverly used as huge water reservoirs some 30 to 40 meters below ground. Diversionary tunnels were dug from the cavities to aqueducts filling the reservoirs, which were lined with lime. This provided a ready supply of fresh water to the buildings above. Other well shafts were dug to give access to the public within the early walled city.

All the buildings in the oldest part of the city had wells to draw water from well pipes, which in time were walled over and served as cisterns.

Hydria Virtual Museum

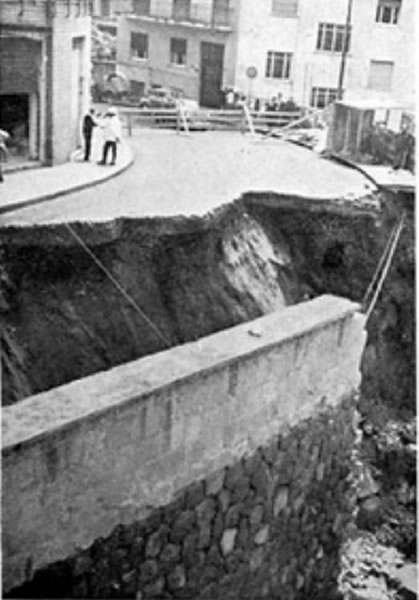

On another point of view, the lack of a complete cartographic map of the immense channels underground Naples city, and the uncertainty about certain subterranean cavities has generated quite a few problems from an engineering and constructive point of view: The presence of many unknown empty spaces has more than one caused in the past the collapsing of above buildings and installations…

Life in Naples

At times when peril and danger came from the sea, Neapolitans would relocate to inland protected sites, but, generally speaking, life developed around the harbour and the shore where economic interest and trade flourished. So, most of the inhabited area that coincides with today’s heart of Naples has always been around the ancient Greek town.

What may seem an unbelievable privilege of taking water from public wells and cisterns, in palaces, even in peoples’ yards and flats, was due to the low flow and minimum slope of the ancient Bolla aqueduct (from 18.5m above sea level at “casa dell’acqua” source to merely 13 m, respectively, at via Tribunali). The flow was thus insufficient to allow the working of fountains that would otherwise consume large quantities of water.

In “vico Pazzariello”, a narrow street in the historical centre, at no 3 in a building of the end of 17th century, later transformed in flats, on each floor, in the narrow and dark corridor, there used to be a well shaft at least until the mid 1960s. It may still be there although water abstraction shouldn’t be allowed after the cholera plague of 1885.

With only a few exempt periods (e.g. between the Byzantine and the Norman domination), the population of Naples has always been fast growing. However, instead of expanding in space, the city went on growing on itself, thank to the fact that its territory is on different levels.

Moreover, contrary to antiquity when building outside the city walls was forbidden, during the Spanish vice royalty (16th century AD) a law forbade the entrance of building materials in the city. That was yet another reason for people to keep on extracting the tuff from the subsoil and use it as a building material. Today when viewing the city from the hill of San Martino or Castel dell’Ovo one can observe a town built on different levels, like a huge stair case.

From the social point of view Naples has always been characterised by a strong division in social classes also in the modern and contemporary age. The poor people live in apartments in the bleak, non-renovated buildings of the city centre, particularly at low levels or ground floor, often in the so called “bassi”, with a door on an alley, as their only opening! Wealthy families, instead, can afford to live in the aristocratic buildings of the historical centre or the trendy districts (either Mergellina and Posillipo by the coast, or on the hill of Vomero).

Certainly, notwithstanding the poor condition of the Neapolitans and the frequent water shortages, the fountains and particularly the underground reservoirs, accessible through the wells, facilitated a lot the city inhabitants in the past: Women were certainly accommodated by having water available even within their dwellings in periods when one had to walk far to fetch water or to wash linen at the public wash houses. On the other hand, for centuries, the way buildings grew has made families to live very close to one another without any privacy.

Of course, the available water was not always safe as it flowed in open or underground channels and could be easily contaminated with all sorts of filth. Often the wells functioned the other way round receiving water from the roofs and streets and only in the best cases their inner part was covered by bricks. The reservoirs were supposed to be kept clean by well workers but this was not always assured. In these circumstances, it comes as no surprise that cholera became an endemic plague in Naples in the 18th and 19th centuries, particularly in the very poor districts. The poor paid dearly for their proximity to water…

The role of water sources at times of war

In order to take possession of the city, many conquerors had the idea to hide in the cisterns and to enter the town climbing from the aqueduct. For example, in 537 AD, Belisarius, who commanded Justinian’s army in the Italian campaign against the Goths, got to Naples and concealed a whole regiment of horsemen in the cavern of Sportiglione, below Capodichino, while he himself set up a camp in front of the gate of Santa Sofia (now San Giovanni a Carbonara).